- Home

- Jennifer Yu

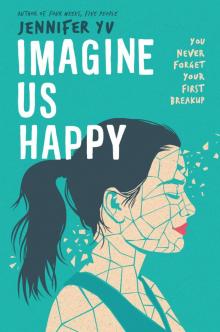

Imagine Us Happy Page 2

Imagine Us Happy Read online

Page 2

“But was it amazing?” Katie says. “Did you discover yourself? Did you, you know, meet anyone?”

“Katie,” I say, very seriously, because once Katie starts talking about boys, it’s very important to rein her in before she goes off the wall. “I was at a camp for troubled teenagers. We were in therapy all day. Not exactly romantic circumstances.”

“Don’t call yourself a troubled teenager,” Lin says. “You’re not troubled. You’re just—”

“Difficult? Emotionally disturbed? Had a complete meltdown in the middle of our American history final for no apparent reason and almost got kicked out of school?”

There’s a beat of silence. “You,” Lin finally says, “are going to have a killer common app essay.”

3.

Every year, without fail, there’s always that one class that you know you’re going to remember for the rest of your life. Freshman year, there was Literature Around the World, which featured eight critically acclaimed novels replete with obscure metaphors for Communism and increasingly depressing monologues given by characters with increasingly unpronounceable names. Then, last year, there was my American history class, which I thought would be a yearlong testament to democracy, innovation and the joys of fried food, but instead ended up being a survey of all the people white men have ever victimized, which, as it turns out, is everyone.

Compared to freshman year English and sophomore year history, the first six classes on my schedule are remarkably uneventful. European History quickly devolves into a never-ending list of petty wars fought by men with large egos and even larger budgets. My decision to take normal CP biology is validated when Ms. Jensen announces that the school has purchased only enough fetal pigs for the AP class to dissect, leaving the rest of us, presumably, to spend yet another year learning that the mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell. Calculus immediately reveals itself to be a joke when Mr. Tang throws his teaching degree to the wind and instead begins bribing the class by throwing candy at the people who raise their hands. In fact, going into last period, the only thing standing between me and a complete roster of forgettable classes is Philosophy, Room A208, Dr. Mulland.

Dr. Mulland is one of those middle-aged guys that seems completely ordinary. He’s of average height and average weight, with brown hair that’s graying at the temples and glasses that look about one size too big for his face. But everyone who has taken his class says that it’s unforgettable, and the administration must agree, because they appointed him the Humanities department chair three years ago. Now it’s almost impossible to fulfill the graduation requirements without taking either his freshman/sophomore history class or his junior/senior philosophy elective.

The first thing Dr. Mulland does when he walks into the classroom at 2:20 is pick up a piece of chalk and scribble, in long, sweeping strokes:

What.

is.

PHILOSOPHY?

He underlines philosophy twice, as if the caps weren’t enough, and then turns to face the class expectantly.

“What is philosophy?” Dr. Mulland asks us. He glances around the classroom and must find something amusing about our blank expressions, because then he smiles, spins around and asks again, this time facing the chalkboard: “What...is...philosophy?”

The unmistakable silence of seventeen students who have just realized that they should have taken the underclassman history class is punctuated only by the sound of Becca Windham sneezing as chalk dust floats into her face.

Dr. Mulland spins around and narrows his eyes at the class. “Jesse,” he says, pointing at a senior in the back row who snuck out of study hall fifty minutes ago and returned bearing the unmistakable scent of weed.

“Teach?” Jesse says.

“What,” Dr. Mulland says, turning around to underline Philosophy three more times, “do you think of our little introductory question here?”

“What do I think?” Jesse repeats.

“There must be something, Mr. Turner.”

“I guess it’s just, like, the study of...things,” Jesse says.

“Things,” Dr. Mulland repeats. “Interesting.” He picks up a piece of chalk and writes that down, next to the question. I stare blankly ahead at the chalkboard, which now reads:

Things.

Is this guy for real? I think. But he must be, because Dr. Mulland doesn’t miss a beat as he turns to Jeremy Cox and asks: “Mr. Cox! What say you?”

Jeremy, a senior on the football team who surely has not been asked to memorize anything outside of a playbook in the past four years, blanches. “Er,” he says. “I mean, it’s just, you know—hey, can I go to the bathroom?”

“I am sure you can but you may not,” Dr. Mulland replies. “Give us a guess, Jeremy.”

There’s a moment of silence during which I become convinced that Jeremy is going to start reciting fantasy football stats. But then he pulls himself together and says: “Trying to find the truth?”

“The truth,” Dr. Mulland says, and writes that up on the board, too. “A noble pursuit indeed—don’t you think, Becca?”

Becca sneezes.

“Bless you,” I say reflexively.

“Ah, but that would be religion,” Dr. Mulland says, spinning to face me. “Closely related—fundamentally inextricable, I’d say—but not quite this class, Stella. You may want to consider World Religion with Mr. Edwards.”

“That’s not what I...” I start, but Dr. Mulland just winks at me and looks around at the rest of the class. “Ashley, you’re up.”

“I mean, you have aesthetics, right?” Ashley Kurtzmann says. “But then also other stuff?”

Dr. Mulland writes:

Aesthetics.

Then:

Other stuff (?)

“Brady!” he says, without even turning around.

“It’s the study of existence,” Brady, class valedictorian and Harvard legacy three generations running, drawls.

“Excellent,” Dr. Mulland says, copying that down. “Someone who read the syllabus. Kevin?”

“The pursuit,” Kevin Miller says, “of wisdom.”

Kevin taps his pencil against the desk once and looks thoughtful. Then he adds:

“At the end of the day, isn’t that what we search for when we study philosophy? What it means to exist. What value there is in truth. Religion. Beauty. Existence. When we find those answers, or, perhaps, what we find instead of answers—it’s all wisdom, isn’t it?”

There’s a moment of confused silence as the class processes the fact that someone has actually responded to Mulland’s question, during which Brady looks pissed that someone has showed up his answer, Jeremy looks even more bewildered than he did before, and Becca looks impressed and...kind of turned on. Me? I’m just trying to figure out who the hell this Kevin kid is, and why he’s so unfamiliar to me. Sure, he’s a senior, but the school is barely 500 people. There’s something about him that should trigger a memory—the brown hair, the shadowed blue eyes, the faintest hint of a smile on his face, as if he’s appreciating the sound of his answer as he says it.

“Thank you, Mr. Miller,” Dr. Mulland says. “And to the rest of the class for participating in my little exercise.”

Then he throws the chalk down on his desk so loudly that half of the front row jumps.

“Philosophy,” Dr. Mulland announces, “encompasses all that’s been proposed today. It is, as Jesse proposed, the study of things—what defines an object, what makes it real, what constitutes ‘being.’ It is also, as Mr. Cox here suggested, the contemplation of truth—whether or not such a thing exists, and whether or not we have any hope should we dare and go seek it. Philosophy includes aesthetics: the realm of art and beauty. And, of course, philosophy includes existentialism, the particular focus of this class—a body of thought that seeks to understand the nature of human life itself.”

Ano

ther pause, during which I begin to understand why everyone at Bridgemont loves this class. I can’t take notes fast enough to keep up with Dr. Mulland’s monologue, so I settle for scribbling down particularly eloquent phrases—Pursuit of wisdom. Contemplation of truth. Hope should we dare. Nature of human life—and hoping that I’ll understand when I reread my notes later.

“Like life, which at its richest is both transcendent and futile, both joyous and damning, the works we will be studying are profound, divergent and contradictory. Our journey begins Thursday.”

Dr. Mulland dismisses us from class twenty minutes early. At our lockers, Lin and Katie ask me how the last period went and I describe Mulland’s opening dramatics in painstaking detail, trying futilely to recreate the specific phrases he used.

“I loved that class,” Lin sighs, looking nostalgic. She has four textbooks in her arms that she can’t put away because Katie is currently using the mirror on the inside of Lin’s locker to reapply her lipstick. “Made me think about Steinbeck’s East of Eden in a whole new way, really.”

“Any interesting guys of note?” Katie asks.

“No,” I say. “But there was this one guy who gave a mini-speech of his own. Something about philosophy as the pursuit of wisdom. Got really into it. Kind of seemed like he’d already taken the class.”

“Was he cute?” Katie says.

“Uh,” I say. I think of the guy from class and his messy brown hair, the slight smirk on his face when he talked about philosophy. “In an artsy hipster kind of way, I guess.”

“Huh,” Katie says. She slides her lipstick back into her pencil case and slides out of Lin’s way. “Well, that’s better than nothing.”

4.

I walk into the house after finishing my run on Tuesday afternoon to find my mom sitting at the dining room table clutching a cup of tea, an expectant look on her face.

“Hi, honey,” she says, before the door has even finished swinging shut behind me. “How was school today? Did you have a good run? Care for some tea?”

Ever since the whole mental meltdown thing happened in the middle of the school year last semester, my mother has gotten really into tea, as if some particularly potent strain of chamomile is going to be able to soothe our family’s nerves back into normalcy. Left to her own devices while I’m at school and my father is at work all day, she’s somehow managed to amass six tea sets since Christmas, not to mention enough tea leaves to get the entire town of Wethersfield through a nuclear winter. I can no longer hear the sound of a kettle whistling without feeling my heart rate triple in anticipation of some serious family conversation that will be, presumably, terrible. The only bright side is that birthday shopping for my mother this year took two minutes flat.

I sit down at the table and pour myself a cup—green tea, I note, and that’s a relief. There’s a pattern to these things: green tea, or anything fruity, indicates that my mother is stressed, but far from peak neuroticism. Oolongs are a step above that: made in anticipation of conversations that range from awkward (“You know, the Kayes down the street mentioned that Brian is looking for a date to the next school dance...”) to verbal waterboarding (“We’re concerned about your grades, Stella. Are your whole...emotional issues...affecting your schoolwork?”). And black? Black teas are the real heavy-duty nerve soothers, which means it’s probably best to just drop a Xanax into the cup as you sit down.

“School was fine,” I say.

“Just fine?” she asks.

I don’t know what it is that parents seem to have against fine. I’m a sixteen-year-old girl living in the heart of suburban Connecticut, whose primary goal for the foreseeable future is to graduate high school without doing anything scandalous enough to become the Wethersfield church crowd’s weekly object of gossip. I’m not sure what part of that seems remotely conducive to a life that transcends the bounds of the adjective fine.

“Yes, just fine,” I repeat. “As in, the idiots comprising fifty percent of my grade have somehow managed to make it out of yet another summer alive, but at least there were no punches thrown today.”

My mom hums a little, sipping carefully. She looks—well, she looks sad, is the thing, which makes me feel kind of sad, too. I know that things with my dad haven’t been great lately, and that she’s probably been sitting at the table for a while, waiting for me to come home, and that I should probably be more—I don’t know, conversational. But conversational has never been my strong suit, and even as I finish my cup and my mom pours me a new one, I’m mostly thinking about how quickly I could pull off an escape to my room.

“How are your classes?” she asks.

“Fine.”

“Anything interesting on the schedule this year?”

“Eh,” I say. “History’ll be boatloads of flash cards as usual. No dissections in biology this year, thank God. The philosophy teacher that everyone loves seems cool, but let’s face it—the class will probably be ruined by all the assholes who are just in it so they can graduate.”

“You should give your classmates a chance, Stella,” my mom says. She smiles a little ruefully, so that her eyes crinkle and the lines around her mouth come out. “When are cross-country tryouts?”

“Friday.”

“You feel good about them?”

“Eh. I feel—”

“Let me guess—fine?”

I shrug. “Coach likes me, I think.”

My mom squints at me. “And emotionally...?”

I shrug.

“You know, Karen mentioned that we might want to consider extending your sessions to three hours each week, or perhaps going twice a week as we enter the school year.”

“Mom,” I say.

“Transitions are tough, Stella, and junior year is stressful. This is the year that your grades really matter, and college—”

“Yeah, yeah, college applications next year. I know. I promise that I’m fine. Going to therapy for three hours a week is just going to make me go insane faster. Then I won’t even make it to whatever colleges I get into next year! Also, I have to go start my history reading so I’ll talk to you later bye!”

The sound of my mom’s sigh follows me up the stairs.

Three hours of therapy a week, I think, after I’ve shut the door, shrugged my backpack onto the floor and fallen into the bed. Jesus.

5. A Brief Explanation

Here is a fact:

Sometimes I just get...sad.

It feels something like this:

Like there’s a black hole in the center of my stomach and it’s pulling all of my vital organs into it and I’m slowly imploding into myself.

Or maybe like this:

Like there’s no point in getting out of bed because that black hole inside me is going to suck everyone else’s happiness into it, too.

Or, one time, like this:

Like the shouting in my head is so loud that I can’t hear or think or read the questions on my American history final so I start screaming on the outside to try and drown out the noise on the inside, but the problem is that everyone can hear the noises you make on the outside, Stella, and now what have you done?

But it’s all right. Because here is another fact:

I’m better now. I swear.

6.

On Wednesday, Katie, Lin and I make the most of what little remains of summer by eating lunch outside. We head to the back of the Lantiss Courtyard, where a line of trees separates the end of the campus from the road on the other side. From here, the only suggestion that there might be more in the world than Bridgemont Academy—more out there than the layers of red bricks towering above us and the tennis courts in the distance and the aggressively maintained grass that fills every possible square inch of space in between—is the sound of rushing cars on the road, filtering through the tree leaves. But even that noise is so constant that it eventu

ally becomes white noise, barely noticeable, a sound that might as well be a part of the school itself.

The courtyard itself is never crowded. Only upperclassmen are allowed to use it for lunch, and most of the one hundred and twenty people in the two classes decide to go off-campus to eat lunch, anyway. Despite the room, Lin, Katie and I sit as far away from the entrance as possible because the only other upperclassmen who stay on-campus without fail are the athletes, who congregate in the center of the courtyard with their protein shakes and loud inside jokes and endless talk of balls and points and players and whatever the hell else. The end of the hour always devolves into yelling as they all abandon their lunches in a mad scramble to figure out which one player’s turn it was this week to do the math homework for everyone else. If only Principal Holmquist knew that this was the “team spirit” his monthly pep rallies were fostering.

“Is it bad that I kind of hate them?” Lin says. She peers over the top of her laptop at the mass of jocks starting to file into the courtyard. Jeremy Cox is there, of course, and his cheerleader girlfriend slash inevitable homecoming queen, Jennie von Haller, then there’s the quarterback Adrian and his girlfriend, then a quarter of the baseball team files in...

“Like, I’ve spent my entire life staying up all night writing papers and studying for tests and doing lab reports and double-checking math problem sets, and then dragging my ass out of bed at 4:00 a.m. in the morning to make it to swim meets, and then forcing myself to stay awake through biology so Jensen will write me a recommendation, and then staying after school for drama practice to develop my creative side so I can be, oh, I don’t know, well-rounded,” Lin continues. “And all Adrian’s done is lucked into being six-three with well-developed biceps and he’s going to have God knows how many colleges just begging him to go there. Where’s the justice in that?”

“I’m not even a senior, Lin, and even I know that there’s no justice in college admissions,” I say.

Imagine Us Happy

Imagine Us Happy